What? The Anglo-Irish Agreement.

Not to be confused with The Anglo-Irish Treaty (1921).

When? Signed on 15th November 1985.

Where? Hillsborough, Northern Ireland.

Why? Both the UK government and the Irish government had been alarmed by the electoral and PR successes of Sinn Féin in the wake of the Hunger Strikes. On top of that, the British government was tired of Unionist intransigeance about sharing power with Nationalists which had thwarted previous attempts to negotiate a solution to the Troubles.

Who? Principally, British PM Margaret Thatcher and taoiseach Garret FitzGerald. More important is who wasn’t there.

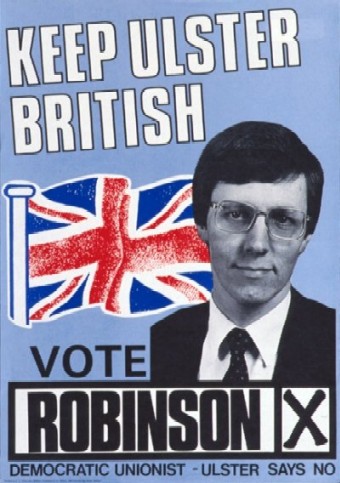

Who wasn’t, then? James Molyneux (head of the UUP), Ian Paisley (head of the DUP), Peter Robinson, James Kilfedder, John Taylor… and indeed any Northern Irish MP.

Why not? You’d have thought they might have had something to say about the matter… That was exactly the worry. The decision to sign what amounted to an intergovernmental treaty over the heads of Northern Ireland’s politicians was intended to prevent them wrecking it as they had the Sunningdale Agreement of 1974.

What was agreed?

The Agreement formally recognised the Republic of Ireland’s interest in Northern Ireland and gave it an advisory role on Northern Irish matters. To those ends, an intergovernmental conference was established to coordinate cross-border cooperation on security, legal and political matters. There was to be a permanent secretariat staffed by civil servants from both countries, at Maryfield, near Holywood, Co. Down. But the most significant item was agreement “that any change in the status of Northern Ireland would only come about with the consent of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland” (Article 1).

And everyone was okay with all that? Ha ha ha. Hardly – the adage “you can’t please all the people all the time” could have been coined for Northern Ireland. The Unionists were furious that they had not been consulted and that a “foreign government” now had influence over their poltical affairs. Sinn Féin opposed it because it accepted the partition of Ireland by formally recognising Northern Ireland’s current status as part of the UK. The main Irish opposition party, Fianna Fáil, opposed the Agrement on the similar grounds that it violated Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish constitution (which claimed sovereignty over Northern Ireland). The Irish courts, however, rejected court cases arguing along these lines.

What happened next? The Unionists adopted their tried and tested tactics of rallies, strikes and civil disobedience. There were mass protests, including a huge demonstration in Belfast, attended by anything from 35,000 to 500,000 people, depending on whose estimate you believe.[1] This demo produced one of Ian Paisley’s most famous pieces of rhetoric:

For a long time after, a huge banner with the slogan “Belfast says NO” hung from the facade of Belfast City Hall.

In December all 15 Unionist MPS resigned their seats, triggering a slew of by-elections that effectively became a mini referendum on the Agreement. (15 of the 17 Northern Ireland seats were held by Unionists at the time). UUP, DUP and UPU[2] agreed on an electoral pact. In each seat the ex-MP would be the only Unionist candidate. The by-elections were held in January (incidentally this is the largest number ever held on a single day) with 14 of the 15 MPs being returned. (In Newry and Armagh Ulster Unionist Jim Nicholson lost to the SDLP’s Seamus Mallon.)

And were the protests successful? Not at all. Though even Thatcher was unnerved by their strength, the way the Agreement had been set up made it immune to localised opposition. She had cross-party support in the Houses of Parliament, the Dáil had also approved it, and international reaction had been favourable. Throughout 1986, protests and violence continued, but the Unionist leaders were in a dilemma. Loyalist violence (which they had arguably incited) was having a bad effect on the image of their cause, and the abstentionist and obstructive tactics they were left with were having little effect. Strikes were not a feasible long-term option in the poor economic climate of the times. A petition with 400,000 signatures (by February 1987) was simply ignored by the government.

And what were the Agreement’s effects? In the short term it made little difference. But with the benefit of hindsight, it can be seen to have helped create the right conditions for the peace process of the 1990s: it established the principle and practice of the British and Irish governments cooperating on Northern Irish matters. It bolstered the constitutional nationalists of the SDLP at the expense of Sinn Féin. It showed Unionists politicians that a failure to engage would simply mean a loss of influence. And finally, it stated the principle of consent as the basis of fundamental change of Northern Ireland’s status, which ten years later became one of the cornerstones of the Good Friday Agreement.